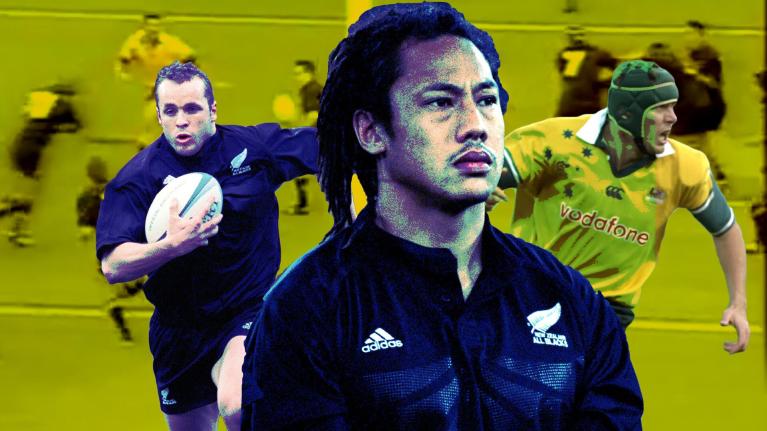

Analysis: Why did the 'greatest set-piece play of all-time' work for the 2000 All Blacks?

Twenty years later it is still regarded as the greatest set-piece play in international test rugby.

During the second test of the 2000 Bledisloe Cup series, the All Blacks pulled an elaborate wrap-play followed by a double-bluff switch to baffle the Wallabies and open them up.

The move went through the hands of every member of the All Black backline off a short five-man lineout and sent the Cake Tin into delirium as Christian Cullen scored his record-equaling 39th test try.

So, why did this play work and how come there aren’t many replicas?

The daring and bold ploy was actually attempted in the first test in Sydney but messy ball off the top of the lineout resulted in some indecisiveness.

Pita Alatini (12) bailed on the pass to Alama Ieremia (13), where the wrap would take place, and instead took a carry into the defensive line.

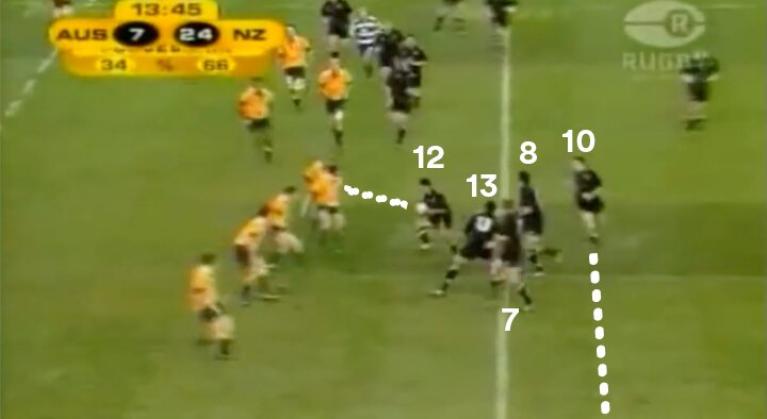

Ieremia (13) is seen in the process of turning to form the ‘pod’, flanked by Scott Robertson (7) and Ron Cribb (8), with Andrew Mehrtens looping around to receive the return ball from centre Ieremia.

The play was disrupted from the very beginning at the lineout where the Wallabies were able to pressure the jumper, Todd Blackadder (4).

The All Blacks have both locks walk into the lineout and sell the jump at the back, with Todd Blackadder faking that way before turning to become the jumper at the two spot.

The five-man lineout can naturally only provide one two-man lift. Norm Maxwell (5) is left unguarded by the Wallabies at the back with only Kees Meeuws (3).

This is an important detail that the All Blacks would later exploit during the successful edition of the play in Wellington.

The ball from the top of the lineout from Blackadder bounces at Justin Marshall’s feet, who is also under pressure, and he delivers a bounce pass to Andrew Mehrtens to add to the disruption.

To get clean ball, the All Blacks took more risk in Wellington and changed up the lineout personnel to get another loose forward involved.

They banked on getting an uncontested throw at the back because where they would only use a one-man lift.

It was a higher risk gamble as one-man lifts are extremely hard on the lifter and result in a lower apex for the jumper. In some cases, they quite literally struggle to get off the ground.

To compensate for the loss of air time, they subbed in Ron Cribb (8) to use his extra height and relied on Taine Randell (6) to make the lift.

This time both locks start in the middle of four-man lineout before bailing towards the front, while Randell walks in late as the fifth man to prepare to lift Cribb at the back.

The Wallabies bite on Blackadder and Maxwell heading to the front, leaving Cribb unmarked.

What is amusing is that halfback Justin Marshall is the proposed lifter at the front, which should have been a tip-off that the ball was not going there as halfbacks never lift locks.

The throw is perfectly thrown over John Eales at the front and the All Blacks get uncontested ball at the back after a Herculean one-man lift from Randell.

The ball off the top from the back allows Marshall to get the pass off from outside the 15-m tramlines and fix the issues of messy ball in Sydney.

The ball successfully and quickly goes through the hands of Mehrtens (10) to Alatini (12) with enough time to pull off the wrap before being met by the defensive line.

Ieremia’s pod doesn’t commit any defenders into contact but successfully propels Mehrtens on the return ball to the outside of defenders Stephen Larkham (10) and Jason Little (12), dragging the Wallabies inside backs into a sliding drift.

All of the Wallabies backs are in a drift pattern, and this is where the All Blacks run a double-switch to exploit that and isolate the middle defender Jason Little (12).

Dan Herbert (13) continued his drift out, creating separation from Little (12) on one side, while Larkham identified the cut from Jonah Lomu (11) early and broke away on the other.

The first switch pass to a rampaging Lomu draws Larkham (10) but crucially freezes out Little (12), who slows to change direction and turns in.

Little is isolated with no outside or inside help having been frozen by the first switch and becomes vulnerable to the second switch-back in the original direction.

Tana Umaga’s (14) timing on this play is impeccable. His trailing support line originally looked like nothing, he was so far behind Mehrtens and the ball he wasn’t an option for the defence to think about.

The switch to Lomu bridges that timing deficit for Umaga and he goes from a half jog to full speed as Lomu plays the pass underneath.

With Little caught still on an island and Umaga turning the corner at full speed, he is able to beat the Wallaby midfielder with a smart fend at pace.

Once in the clear, Umaga draws Latham and puts a looming Christian Cullen (15) in untouched.

The move was complex as it evolved but rather simple at the targeted incision point once the one-on-one matchup was achieved.

The Wallabies defence was always in trouble as they never took forwards out of the lineout to match the numbers taken out by New Zealand.

The All Blacks effectively ran a four-man lineout but Australia had seven men there, which became a huge disadvantage once they had successfully schemed clean ball at the back and attacked left.

It is easier to think of the pod in the midfield around Ieremia like an ‘accelerated’ ruck that didn’t go to ground and everything after that was like a planned second phase play going the same way.

The pod held play up long enough for Mehrtens to get around the corner but was too fast for any Wallaby forwards to fold.

Samu Kerevi often has had a similar impact for the Wallabies with his ability to carry strong and find an offload off the deck to create quick ball.

When you see how effective this 'accelerated ruck' pod could be, you wonder why so many teams persist on running midfield crash balls, going to ground and recycling before going wide. If you could get the ball there faster with more numbers, why not try to do that instead?

The double switch may look like an over-engineered play, but it had the desired impact of instilling indecision in defenders and creating a mismatch between dynamic athletes in motion with stationary men.

Switch passes, and certainly double bluff switches like this one, have almost become extinct in the modern game but could return to help combat the seemingly impenetrable rush defences around today, particularly around the ruck area.

It still remains one of the greatest set-piece tries, but also one of the great team tries of all-time at Test rugby level - and those tasked with trying to unlock defences today should review some of the concepts used to try come up with more creative plans than currently used in the game today.

Crusaders' media session with Mark Jones:

Latest Comments

And the “experts” from NSW still bang on about not having enough talent in Australia to maintain a 5th super team. There’s plenty of talent like this guy. Just have a look at the player rosters in France and Japan. Hell, even the French academies are signing up young aussies. They just need to sort their pathways, opportunities and player retention which is often thwarted by the comically poor, shoot themselves in the foot decisions made in Sydney.

Go to commentsEasterby and Goodmna are utterly useless.

Then being gone can only help Ireland in the lkng run

Go to comments