'The beautiful game is replaced by hard rugby, by the taste of blood in the mouth.'

It’s a well-worn cliché from British rugby fans that French rugby can be a little, well, crazy, their Latin temperaments on occasion forcing them into making emotionally charged egregious decisions, leading even one of their greatest generals, Pierre Berbizier to once remark ‘France’s greatest adversary is itself’ but it is also true that this unpredictability and joie de vivre has spirited them to three World Cup finals, the first of which was in 1987, where against the odds, they beat Australia with Serge Blanco’s breathless sprint to the corner.

Even though that side lost 29-9 to New Zealand, having spent six weeks away from their families and places of work over 10,000 fans turned up at the Charles de Gaulle’s airport in Paris to welcome their heroes back.

What forged the men who terrorised and thrilled the rugby world in equal measure throughout the Eighties is studied in great depth by first-time author, David Beresford, a former rugby player, bon viveur and Francophile who spent nigh on two years travelling all over France to interview the iconic names of the era. This was made possible after a company flotation that left him with a generous window with which to make numerous trips to France. Superstars Serge Blanco, Philippe Sella and Jean Pierre-Rives all offered intimate insights into their personal lives for his opus called Brothers in Arms, which was shortlisted for rugby union book of the year at the recent Sports Book awards. Beresford didn’t just want to talk to them about their on-field career, he wanted to delve deeper to discuss humanity and its kaleidoscope of colours.

At over 400 pages, it is very much a long-lunch of a book; no snatched hours with one high-profile subject for a rapidly-assembled autobiography, but a selection of lovingly crafted vignettes after speaking to over 140 interviewees. In all it clocks out at 150,000 words of prose that meander from region to region in France with fine food and wine as an hors d’oeuvres to untold stories, which add to French rugby’s rich tapestry.

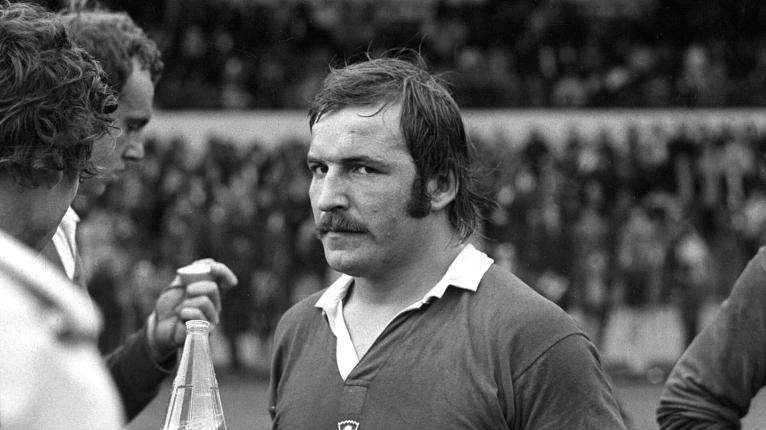

With stunning portrait photography from Pierre Carton, it uncovers what really motivated Jacques Fouroux’s men in a period where they won Five Nations titles and two Grand Slams. We uncover the childhood struggles that forged their characters and what stood out above all was the enduring love they had for one another.

Speaking to Beresford, a former centre, from his home in Bath, he was keen to explain, first, why rugby had taken a foothold in France, and particularly in the heartlands of the south.

“The way Valerie Paperemborde, Robert’s lovely widow described it, was that rugby in France about terroir, loosely the earth or soil that defines you and a village’s ability to forge a unique identity. It caught on in the south because it allowed people to express their independence of spirit, as opposed to in England, where perhaps it was more about instilling discipline and fitness within the strict confines of the public school system.”

Like England, rugby’s roots had emanated from educational establishments but soon germinated far beyond the stuffy academic institutions. “The first club was formed in Le Havre, but from there the game migrated to some of the Grande écoles, and Lycées in Paris. Racing Club of Paris (now Racing 92) was born out of a very prestigious Lycée but it soon travelled South and settled at the foot of the Alps in Grenoble. Before long with word spreading, rugby union pinned its ears back and headed South-West, to the Atlantic and the Basque stronghold of Bayonne and l’ovalie (the oval ball) really took off.”

At the time, Bayonne was primarily a rowing club looking to offer more sports but the introduction of rugby strongly resonated with Basques. In essence rugby was about spirit and independence. It suited the rustic farmers of the South who were working the land. Beresford says what really cemented union’s purchase on the south was when rugby league was banned after the Second World War (WW 2). This, he surmises, is the logical view but there are many idiosyncrasies that are harder to explain. “Why have you got such a strong club in Toulon? It’s in the blazing heat of the South of France with only the Mistral to soothe overheated players but the Toulonnais love the physicality of rugby and its warrior-like traits. The heavy smattering of navy and military bases down there helped embed it into the force we see today. From there, if you headed inland and clubs like Agen, North of Toulouse and you would find cultural differences. The people are super-conservative, gentlemen farmers who don’t want to put up their dukes to everyone.

So how on earth did La Rochelle, with its coastline being thrashed by the Atlantic, become a rugby stronghold? “La Rochelle is so enamoured with the game because Basque fishermen used to head up to the Bay of Biscay, stop off and it seemed to populate the surrounding area. Then there’s Clermont Ferrand in the middle of the Massif Centrale, where the top brass at Michelin loved rugby and encouraged talented rugby players to visit and find work there.”

While giving this fascinating history lesson into rugby’s roots, which digs deep into France’s rugby heartlands, fast-forward to the Eighties and Les Bleus were enjoying a grande époque. They lost no more than one game in the Five Nations in a decade, and at its crux was Jacques Fouroux, head coach from 1981 to 1990. “Jacques was this extraordinary character. He knew exactly the right buttons to press and how to pick the right team,” explains, Beresford. “He had a particular view on who would be there in the trenches fighting and consequently amassed players of the right characteristics. To the forwards, Garuet, Doxpi, Lorieux, he would verbally and viciously abuse them telling them they were crap in the last game and their opposite number was far better than them until they went nuts but to Blanco, he would humbly say, ‘Thank you Serge. Thank you for being with us here today’. He was a genius.”

Another thread that knitted the squad together was their humble formative years. “Take Serge (Blanco), his father died in Caracas when he was two and his Basque mother took him back to Biarritz where he lived an impoverished childhood. Then you have Eric Champ, Laurent Rodriquez, Didier Codorniou and Pierre Dospital who hailed from the foothills of the Pyrenees. These boys had it tough. Several of their families were Spanish, who fled poverty in Spain and latterly the repressive Franco regime. They had basically walked across the Pyrenees because that was the only way they could reach safety. Those survival instincts and mental toughness were passed down a generation.”

The squad wasn’t solely made up of brawlers and ballers, however. There was a tranche of players who were from more refined backgrounds. “Franck Mesnel, Patrice Laquisquet, Denis Charvet, Jean-Baptiste Lafond, Daniel Dubroca – these guys had a very middle-class upbringing. Philippe Sella was from well-to-do Agen farming stock then you had Rives who was introspective but had learned how to convey his message on the pitch quite brilliantly. He is a clever man with a wonderful way with words; an intellectual with a certain je ne sais quoi.”

Leading up to the 1987 World Cup final, France had been led by Philippe Dintrans, a grizzled front-row but due to injury, Albert Ferrasse the influential FFR Chairman (Fédération Française de Rugby) inserted a fellow Agen man, Daniel Dubroca in the role. He was a thinker, incisive and a natural leader. Adding to the intellectual property on the field, you had ‘Berbiz’ (Pierre Berbizier) who was a teacher by training and nicknamed, ‘Le Stratege’ (the strategist) by many. He did most of the talking on the field and even decades later was insistent that he chose where he was placed in the book, which is split into geographical areas the players originate from, ‘I am from the mountains, not the Basque country, the Pyrenees are where my heart is,’ he said forcefully.”

Brothers in Arms has natural bonhomie and empathy and veers away from solely concentrating on rugby, but instead studies human fortitude, with tales of giddy highs and crushing lows. Beresford says one tear-jerker comes from Pierre Dospital, the famous Bayonne prop. “A born and bred Basque, Pierre lost a child at seven from a blood-clot and his wife well before her time and his story pulls on the heart strings. Another fascinating character is the aforementioned Berbizier who divides opinion like no other. Even now, some players don’t talk to him and he doesn’t talk to them. I tried to get into the heads of players. I mean, unless they’ve seriously maimed you or had it away with your wife, why is it so important years later that you still don’t talk to a team-mate?”

The most infamous member of the 1987 World Cup squad was Marc Cecillon who shot and killed his wife in 2004. Cecillon plunged from the highs of 47 caps for France and two World Cups to the depths of depression. He was the one player who let Beresford know he wasn’t enamoured with his entry. “I talked about his time in prison, how he dealt with it and how he’s tried to rebuild his life. It’s a very painful and raw but it’s Marc’s story and I couldn’t ignore it. He seems happy with a woman he met while in prison but he still has his challenges with drinking. In 2018, he had a job on a vineyard but got roaring drunk after harvest and beat his boss up before driving away in his van and crashing it so he got another 12-month suspended sentence.”

Having spent time with him, Beresford came to some conclusions. “Personally, I don’t think he’s really dealt with what he needs to get his life back on track. He hasn’t figured out what to do to reconnect with his daughters who have disowned him. It was the hardest entry to write, without doubt but what I would say is the compassion he was shown by his former team-mates was startling, Eric Champs said this. ‘Marc was a fabulous player, but one day your career is over. You have the limelight for a period and then the light goes out. If you don’t have the right environment to support you, things can turn sour. Those around him should have told him some hard truths and not said, ‘come and have another drink.’”

Another barely believable story is that of Beziers and France prop Armand Vaquerin. One of the most decorated players in French rugby history, Armand was a huge character, a free spirit who lived life to the full but he killed himself playing Russian Roulette in 1993 in a bar in his home town. “He won the Championship 10 times with Beziers in the late Seventies and early Eighties and won 23 caps for France. He’s an old-fashioned prop who probably wouldn’t have existed in the modern era. I went to visit his brother, Elie, who is still haunted his premature death.”

What struck Beresford from interviewing 32 French internationals, face-to-face, was their sense of brotherhood. To a man, they all talked about sacrifice, friendship, fraternity in a way he’s never heard English players speaking. “The way they express themselves is much more poetic and emotional. The bond between them was incredible. The great Patrick ‘Le TGV’ Estève, said, ‘there is no place for an emotional or collective mediocrity to be successful. You have to love each other. Jean Pierre-Rives told me, ‘I wasn’t so much in love with the game, but I loved the men I played with and their friendship. The game is a pretext to make lifelong friends.’ Just wonderful.”

The philosophical and at times, casual menace of the men who had worn the Tricolore into battle was something that really struck the author. “That old rabble-rouser Champs personifies this attitude beautifully. In England’s eyes he was often the villain of the piece. When talking about a must-win games, he didn’t hold back. ‘the beautiful game is replaced by hard rugby, by the taste of blood in the mouth.’ It’s like Napoleon speaking,” exclaims, Beresford.

Then you had the squad’s energisers. Laurent Pardo’s friendship with the players is remarkable and Eric Bonneval and Denis Charvet are the same. Jean Baptiste-Lafond was flown out to Auckland more to cheer the players up even when he was nursing an injury and more inclined to visit the drinking spots of New Zealand.

As for French rugby’s hard-earned reputation for violence, Beresford said on reflection there were no apologies, just a feeling that the ‘bagarres’ (fights) were intrinsically linked to passion and pride in defending one’s honour and by proxy your family and local area. “That was just the way it was. The only people who expressed regret in any form were for very personal reasons. Marc Cecillon didn’t admit it, but regret was etched all over his face. To a man, they all talked very proudly about getting the shit kicked out of them but serving it back with interest, with one particularly gory entry, from Jean Pierre-Garuet, highlighting revenge on Mark McBain, the Wallaby hooker, after Berbiz had been given 38 stitches and Michel Crémaschi’s jaw had been broken, ‘McBain went through the mixer and the grass turned red.’”

Of course the most notorious incident of the Eighties and a theme throughout the book was the Battle of Nantes. It reads like an Hercule Poirot Who dunnit? “It was the great mystery who tore Buck Shelford’s scrotum sack. Some say it was Dominique Erbani, but he denies it and some say Érik Bonneval, but if you knew him you knew it couldn’t be possible but Daniel Dubroca, well though he denies it, the evidence suggests it could well have been him. He was a gentleman farmer but he was one hard man who never took a backward step. To him, it was all about winning. I spoke to Buck about it and he tells the story of two incidents on the pitch. In the first he was gathering the ball on his line and he saw Garuet flying at him horizontally through mid-air, all 18 stone of him. When he made contact with Shelford’s face, teeth went everywhere and the No 8 was attended to for two minutes. On coming round Shelford said that Jock Hobbs, the New Zealand captain, had muttered, ‘you can’t go off because we haven’t got any substitutes’. In the second-half, Buck was cradling the ball, and said Dubroca was on the floor himself when he kicked him in the bollocks. Buck told me he thought it had hurt, but it was only when he got back in the changing room, pulled down his shorts and the other players saw a testicle hanging out that he saw the damage done.” Sacre bleu.

Writing a foreword for the book was 92-cap All Blacks legend Sean Fitzpatrick. The hooker had infinite respect for that French side. “Fitzy talked to me about the Battle of Nantes. He said the French hit them so hard they just couldn’t get a handle on the game. After his first cap against the same French side, the hooker admits the French pack’s reputation preceded them. ‘I was shitting myself in the changing room. We knew how good they were and in the first scrum they hit us so hard it was like being in a washing machine.”

Since self-publishing the weighty tome in December 2019, Beresford, a French graduate with a First Class Honours degree from Loughborough, has been overwhelmed with the reaction, especially in France. “We have about 5,500 French rugby fans on Facebook. I got one message back from the nephew of Pierre Lacans, the frizzy haired Beziers and France backrow who died in a car-crash in 1985, aged just 28. I had visited his mother and was worried what I was going dig up from the past but she was so proud her son had appeared in a book next to the likes of Rives, Blanco and Sella. She thought everybody had forgotten about Pierre, so to see this English chap pitching up wanting to talk about her son, well she couldn’t quite believe it. Her nephew said the book had lifted her spirits immensely. It’s when I get personal messages like that that made the toil worth it.”

With French rugby as unpredictable as ever, the author ends the book on a defiant note. He encourages French rugby to stick to its independent train of thought that so intrigues and befuddles the British. “Dear FFR, please ditch the conventional wisdom, stop copying the Anglo-Saxon way and play to your instincts. Your best rugby is played by artists not scientists, crafters, not grafters, rule breakers not rule takers.”

I think many rugby romantics would raise a glass to that sentiment. Salut.

David Beresford’s 32-man French squad; Serge Blanco, Jean Condom, Pierre Dospital, Patrice Lagisquet, Pascal Ondarts, Laurent Pardo, Laurent Rodriguez, Louisou Armary, Pierre Berbizier, Philippe Dintrans, Patrick Estève, Jean-Pierre Garuet-Lempirou, Alain Lorieux, Érik Bonneval, Daniel Dubroca, Dominique Erbani, Jean-Patrick Lescarboura, Jean-Luc Joinel, Philippe Sella, Robert Paparemborde, Pierre Lacans, Armand Vaquerin, Denis Charvet, Jean-Baptiste Lafond, Franck Mesnel, Didier Camberabero, Marc Cecillon, Eric Champ, Didier Codorniou, Jerome Gallion, Jean-François Imbernon, Jean-Pierre Rives

Coach: Jacques Fouroux

To purchase; Brothersinarmsbook.co.uk (any profits raised from the book will be split equally between the UK Sepsis Trust, The British Heart Foundation, 40tude: Curing Colon Cancer, The Stroke Association)