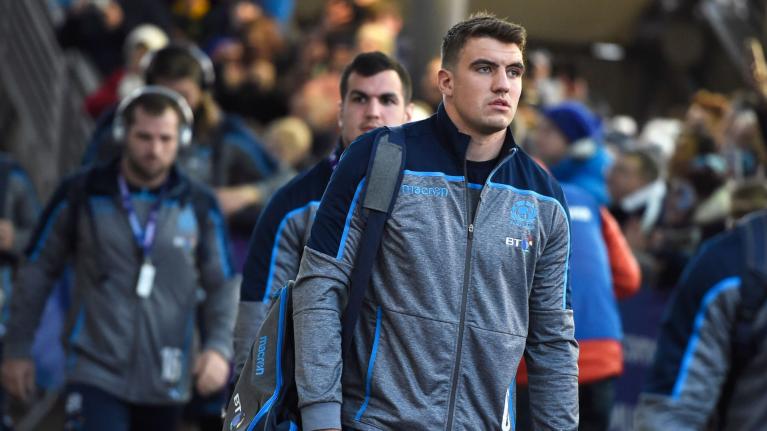

'It was just pure, sheer devastation' - How Sam Skinner dealt with the worst news of his career

In the office of Britain’s top hamstring surgeon, the news struck Sam Skinner harder than any opponent, a double-dose of reality that left him feeling like the entire England pack had just trampled over the top of him.

Deep down, despite the little fibs he’d tell himself, he knew it was coming. And now, the last vestiges of hope to which he had clung were obliterated.

WATCH: Get the lowdown on what your favourite rugby stars are up to in isolation with the premiere episode of Isolation Nation.

The muscle the Exeter Chief had damaged on duty for Scotland against France a week earlier would need surgery. His World Cup? Gone in the blink of an eye.

“I felt I was playing the best rugby of my career to date,” Skinner says. “It was just pure, sheer devastation.

“When it first happened, it was all just a shock. You sit in the physio room and hear Murrayfield going up and the main focus is the boys winning the game. But then it really starts to sink in when you’re sat in the changing room, the adrenaline goes and you realise how sore your leg actually is. I just knew it wasn’t going to be a couple of weeks out when I couldn’t walk.

“There’s always hope, I was hanging on to hope for a couple of weeks that if I still trained hard, worked hard, maybe I could get called out.

“But when the top hamstring surgeon in the country says, ‘No, this is the situation – fact’... well, that’s that done then.”

Skinner, a dynamic thoroughbred forward equally adept at lock or on the blind-side flank, has masses to like about his game. His line-out streetsmarts and leadership, his ballast about the paddock, and his ferocity in the collision are hugely prized by Gregor Townsend. The smart money was always on him making the plane.

When the surgeon finally pierced that dream, Skinner made two calls – the first, to his parents and most emphatic supporters; the second, to his old university pals in London. They made damned certain there would be no slide into melancholy.

“Oh, you’re not going to the World Cup?” one said. “No worries, mate. Crack on.”

A night of Guinness and craic in the big smoke beckoned. It was a blessed release.

“I went straight to the pub and had a few pints,” Skinner says. “Obviously not good for the hamstring but mentally, it was exactly what I needed.

“It was a really nice evening to take my mind off what was the worst news of my career. In the grand scheme of life, and compared to everything that’s going on just now, it’s not a big deal at all, but it felt like a big deal at the time.

“I didn’t get smashed, I just had a couple of beers and it was more the camaraderie with my old uni mates. They’re not in the professional rugby environment and it was nice, being in a whole different little bubble in a pub in London.”

Six months out of the game gave Skinner a rare chance to attack his weaknesses. He rebuilt his hamstring strength, of course, but he could also solidify his core, refine his slightly crooked and aching shoulders. These were tangible, physical steps on the path to recovery, but he began to hate the fact that he wasn’t out there in the trenches, toiling for his mates.

“You sort of feel out the game when you’re not playing,” Skinner says. “You feel less required. The way I dealt with that was helping the team as much as I could with analysis and that sort of thing. I wanted to help the team move forward, I didn’t like not being able to help.

“I’m not alone in saying that when you’re in rehab, particularly long-term rehab, you can feel neglected and you can feel a little bit less important.

“The way I combated that was by talking through line-outs with some of the forwards that were playing week in, week out, offering my perspective.

“A lot of the players are so busy with playing and doing other things that I could take some of their time and help them out with certain things and give my opinion, and that not only helped me but I’d like to think it helped them too.”

Almost eight months since his hamstring erupted, Skinner has won back his place in the Scotland squad, if not quite reasserted himself as a first pick in a ferociously competitive Chiefs pack. The coronavirus pandemic has put a hold on all of that for now, though, and it has also brought the perilous financial state of so many grand rugby institutions into sharp focus.

Among England’s elite, Exeter are perhaps best positioned to weather the storm, but the storm is coming nonetheless. As a rookie, Skinner took time to grow into his physique and blossom into a Premiership-calibre operator. He had nearly given up the game to go travelling when the Chiefs gave him a contract and he went off to study at the University of Exeter.

In six months, he was “locked in the gym”, taught how to lift and eat, and his weight rocketed. From 90KG, he filled out to 105KG. His one-rep max on the bench press soared from a feeble 80KG to a respectable 120KG and he could rattle out pull-ups where before he struggled to manage one.

This partnership between university and club has long been fruitful. In such deeply strained times, might more top-flight teams follow suit?

“It’s a great idea,” Skinner says. “Exeter have had some success based on the university and it’s worked both ways because if you’re an aspiring rugby player who still wants to push on with your degree, as I did, and you know Exeter University are closely linked to Chiefs, it’s going to be a factor in choosing that university.

“That’s brilliant for the uni and it’s also brilliant for Chiefs. The club have got a player they can see for three years and allow to develop.

“There’s no denying one of the big factors in why it appeals to clubs – it’s cheaper. You don’t need to pay a student to come to the university unless you want to because they’re that good. They can then pop into the club now and again, you don’t need to pay that player a lot, and they are still in your catchment zone. In my opinion, there are barely any negatives and a lot of positives.”

Latest Comments

Mzil, I only recently learned Hodgman was only 31 myself, so you’re certainly not alone there!

Canham is a good shout, and he’s coming along nicely in new colours - as is Darcy Swain for that matter.

Whether Gleeson and Hooper feature this year, without a return date confirmed (despite best intentions) remains to be seen. Different to Ikitau, in that we know he’ll return after the Exeter stint and for how long.

And Tizzano will certainly be there. I didn’t need to include him here, but he’s just no longer a fringe player!

Go to commentsYep. The general game is without any rock star 10’s at the moment. Albornoz and N’tamack are about the only test 10s now that have something. Albornoz is probably the only one who even carries to the line these days.

I think D’Mac is a gifted player but a natural 15. It doesn’t really mater now. They just need to stick with him as any player will improve in their position with a run of games in that coaching environment. A steady 7/10 can be enough.

I know he’s divisive amongst Kiwis but he returned from an ACL at 23/24 yrs which takes a lot. He’s got my full respect for that.

Go to comments