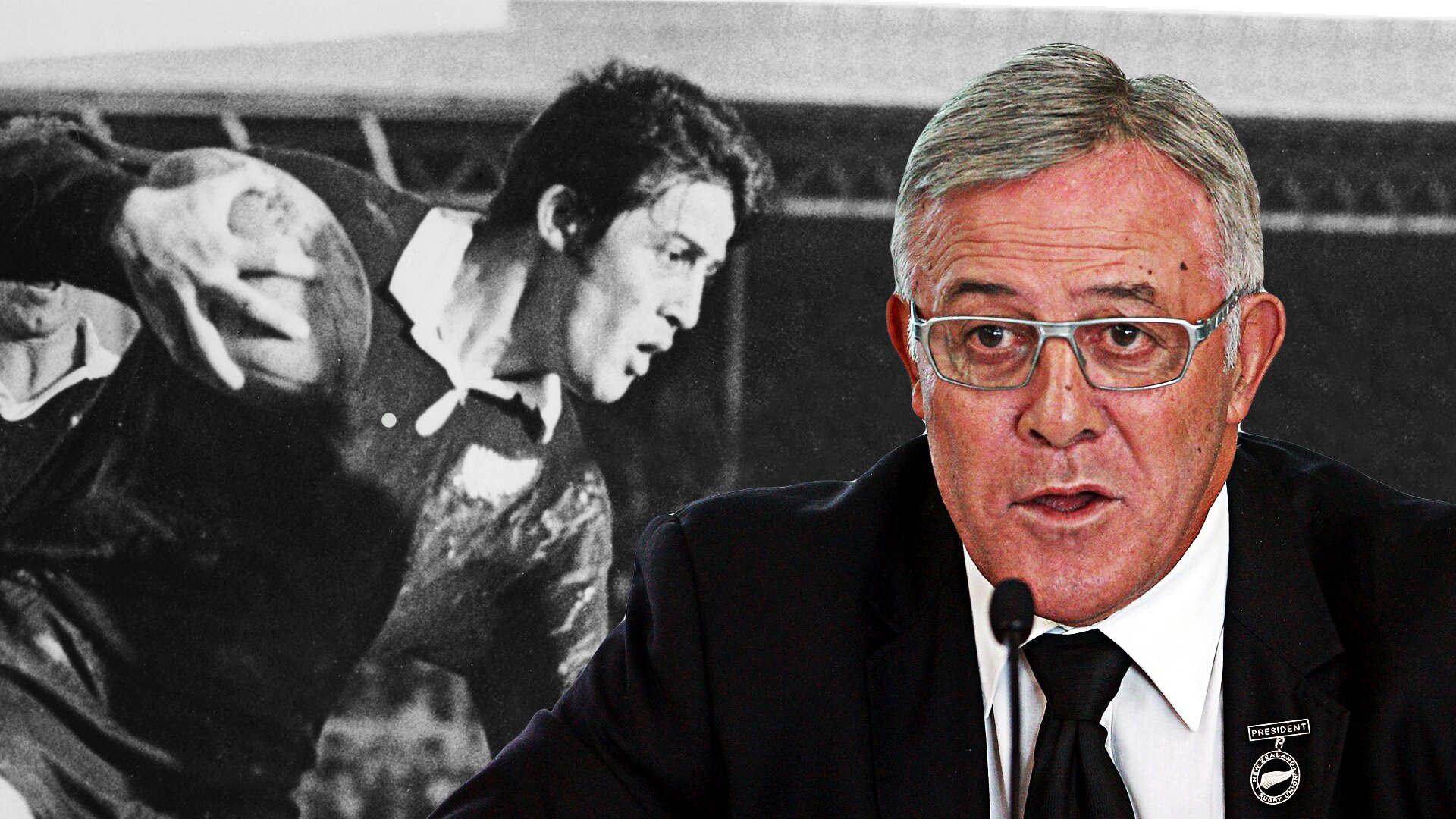

In Conversation with Sir Bryan Williams

In the first part of Scotty Stevenson’s new series “In Conversation…” RugbyPass catches up with Sir Bryan Williams.

When Williams debuted for the All Blacks in 1970 he became the first player Pacific player to represent New Zealand in rugby. He played 38 tests for the All Blacks scoring ten tries. After his playing career, he went on to coach Samoa. He is a proud representative for the Ponsonby Rugby Club.

Last year was a big one for Sir Bryan Williams, he received a knighthood for his services to rugby and was inducted into World Rugby’s Hall of Fame.

Scotty spoke to him about the significance of his 2018, playing in Apartheid South Africa, and the legacy he has left on rugby.

Listen in the player here or read the transcript below.

Subscribe on iTunes here so you never miss an episode.

Scotty Stevenson: Joining us today is none other than Sir Bryan Williams, Beegee, good day to you and a happy new year to you. How are ya?

Sir Bryan Williams: Good Sumo, and happy new year to you and all the listeners. I’m very good thank you.

Thank you very much Sir Bryan. Look, first of all, lets cover the knighthood – what a moment for you, and richly deserved might I add.

Thank you Sumo, you call me Beegee mate, all my mates do and you’re my mate. But it was a special occasion for sure, and I guess you live your life and sometimes these things come along and it was a big thrill at the time for sure.

You’re humble to the end Beegee. The purpose of today really is to have a conversation about what rugby has meant to you, some of your experiences of the game and I think among your generation Bryan you hold such a unique position and some of the things that you in particular have experienced and the pathways you have forged. Did you think about it as a young man Bryan that you would be as trailblazing as you were as a rugby player and as a member of the All Blacks side?

Not really Sumo, I think it was always a great dream to be an All Black and to play at the highest level but you just take one game at a time and back in those days we played club rugby and then provincial rugby and then international rugby, and if you were fortunate enough to climb through the ranks then you had the sort of career that I was able to have. All the travel, all the mates, all the wonderful experiences that we had. At the same time, the game was amateur and we had to forge our own lives to make sure we earned enough money to live.

Exactly right, it was very different mate, and I don’t need to point out your career to you because it was quite something: 113 All Black matches, 38 test matches among those, 75 games for the All Blacks, 71 points in tests – for most people, even though you made the Auckland side in the late 60s as an 18 year old, it was that 1970 tour that really put you firmly not just on New Zealand’s radar, Beegee, but on the world’s radar. Your memories of that tour, and not just on the field but everything politically that swirled around your involvement on that tour?

Well it was a very daunting time I’ve gotta say. I’ve said it before: not only for the fact that I was a new All Black and obviously playing alongside people I’d grown up idolising – the Colin Meads and Brian Lochores and Ian KirkPatricks, and so many other great names of the 1960s, that was one thing. And on the other hand the fact that I was one of the first formal players of coloured blood, for want of a better term, to be selected to go to South Africa, apartheid was obviously a great concern certainly for me and I’ve said it before and again, when the plane touched down in Johannesburg I had this panic attack: suddenly it all hit me, what was going to happen next, what fate was going to befall me once you go into apartheid South Africa. But in the event I took one step after another and suddenly I was playing my first game and scoring my first try and then I was away really.

Were you aware, and I guess you were otherwise you wouldn’t be having a panic attack, but were you aware of the significance of you being on that tour, and what roads that might pave for others in later times?

I don’t think I was aware but I was a law student so I like to think that I had a social conscience shall I say. But no, I didn’t quite realise the significance of it all and I guess as time went by we had the fateful 1981 Springbok Tour and Nelson Mandela being released from Robben Island and becoming president of South Africa, so I guess it was only in later life that you realise the significance of it. It just created a small dent in the armor of apartheid that they were willing to accept four of us as the first coloured players to go to South Africa, and that had some impact down the line.

The career as we mentioned before was significant for so many reasons, Beegee, not just your ability to score tries but the way the All Blacks played the game at that time. I looked at the test in Pretoria on that 1970 tour and names like Fergie McCormack and Dick Thorn, McCray, Cottrol, Ladelaw, Lahore, Kirkpatrick, Straan, Smith, Miller, Hopkinson – these were big names and tough men, but it was a very mixed team for it’s time wasn’t it, when you consider the likes of you and Chris Laidlaw who were very studious, university men, and the likes of BJ lahore, now Sir Brian Lochore, who was much more a country man, dyed in the wool. Did you enjoy the mix of people? Because you’d grown up in urban Auckland.

Yeah I did it enjoy it, but I wasn’t probably aware so much of the differences. As I mentioned, they were my heroes, and that was a difference. I was just a novice, a little polynesian kid from Auckland, and these were my heroes so that was the biggest difference. As time went by I started to realise that we are all from different necks of the woods, and it’s how you all come together – the common bond is doing the best for the All Blacks, doing the best for New Zealand, and that does bind you together. But I think as time goes by you realise that Grizz Wiley and me for example were like chalk and cheese. We became great mates and still are, but just from totally different lifestyles.

I want to go forward eight years and I know I’m cutting out a lot of time in your career because there’s so much more to discuss about the All Blacks, but there are other things that I think are just as important to you and your life. I think about who you started playing with, and then your final test, which was against Scotland, part of the Grand Slam winning All Blacks side of 1978, the first time the All Blacks had achieved that. There had been an almost entire turnover of the playing roster apart from you. You were the sole survivor from that 1970 era through into 78.

Yes, you’re right I guess. The 1970 team after that tour, most of the players who’d carried the All Blacks through a pretty successful era of the 1960s all retired. I found myself in 1971 for the Lions tour one of the more experienced players in the backline, and you know that was pretty hard to deal with at the time. By 1978 as you say many of the players who’d played in 1970 were long gone, and in fact I think they’d all long gone, and so had many of my contemporaries of the early 70s as well.

It was a stunning career and then of course you enjoyed a law career as well for a long time. But one thing you never lost was affiliation to club and the time you spent and still spend with the Ponsonby club. I think that’s what most of us treasure you for, how much you’ve given back to that level of our game. Were you aware that that was something you wanted to do, or was it something you felt you had to do?

Definitely something I wanted to do. Ponsonby was in my blood and in my bones and family affiliations – many of the people I’d grown up with and many of the people I respected were Ponsonby members – so it was very easy to stay involved. I’ve gotta say that the main reason is I thoroughly enjoyed all the interaction that goes on between the different age groups and the different ethnic groups and club rugby is just the tops as far as I’m concerned. You’ve got players from all different walks of life, different abilities, different sizes, all coming together and when you all get together on Saturday and Saturday night at the club after a successful or unsuccessful day, there’s nothing like it. I love it.

Family has been very big for you mate as well. Your boys have launched their own rugby careers. Did you always imagine that the boys would follow in your footsteps in terms of footy?

I guess I hoped they would, possibly I put a bit of pressure on them early, but I soon learned Sumo that I was better, as my darling wife assured me, keeping my mouth shut. That was probably the best option. So I learned that relatively early in their careers. I used to offer advice and the boys would say ‘shut up dad, what would you know?’, so I’ve gotta say once I learned to keep my mouth shut our relationships improved and we’re still great mates nowadays. My wife has been part of the journey the whole time I was at the top level. We started going out when we were 17 years old, so she’s been very much part of the journey and still is.

She’s a remarkable lady of course and that support, especially in your era of the game, it would have been tough. Unpaid, away on tour for long months on end, how did the families get by in those All Black teams?

You’re right. The clubs particularly in the early tours used to band together and raise funds in a strictly amateur era which was probably against the rules but that was turned a blind eye to. Generally speaking, particularly in my later tours, there wasn’t that sort of support coming from the club and elsewhere, so you’ve had to make ends meet. I was fortunate in my early legal career to have an employer who helped me out. Later on my partner Kevin McDonald also had to hold the fort while I was away so I had great support and my wife was also teaching through part of that so she was able to earn some income as well. But as you say, in the amateur era, you just have to make ends meet.

Your connection with the game is so strong and as a rugby player that’s one thing that defines you, but also your Samoan heritage defines you. What was it like to be a young kid of Samoan heritage growing up in Auckland at the time you did?

It was a really interesting time. It wasn’t very fashionable to be an Islander in New Zealand in those days, in fact there was probably a bit of a stigma attached to being an Islander, so what I’m particularly proud of is the fact that the young Polynesian rugby players and netballers and rugby league players and many of the sportspeople have helped break down that sort of stigma over the course of time to the point now where most of our sports have many Polynesians playing the game at the top level and it’s very much part of the scene now. But it certainly wasn’t when I started.

No it wasn’t, and those of us in New Zealand will understand the various racist policies of our government during the time and through the 70s, dawn raids and so on. You would have lived through that Beegee in your humanitarian capacity and your capacity as a citizen of Island heritage – that would have been a particularly trying time as well.

Yea it was a trying time no doubt about that, and when one considers the history of Samoan-New Zealand relations and the various things that have gone on in the past, it was very hard to take, but that was the way it was and you could protest as much as you like but the government was the government and that was their policy, so we just had to make do.

It’s interesting for me, I’m a young male of Pakeha descent, so I don’t understand how tumultuous that must have been for you, and I don’t think many people of my ethnicity would. The fact is I think if I can put words in your mouth you could compartmentalise parts of your life – your law career, your rugby career, your cultural identity. You’ve always been able to make sure that each is in its place at the appropriate time.

You’re right Sumo and I guess it is a trait of mine to compartmentalise it as you say. I sort of think of my life in terms of compartments or chapters and I like to finish one thing and put it away and finish the next thing and put that away, and I guess one of the other key words of my life has been balance. Just getting the balance right. Sometimes things go for you and sometimes they don’t, and when they don’t you have to figure out ways to set things right and straight again and as I say it’s been my philosophy for many years.

I do want to touch on one other thing about your playing days before we talk about your subsequent life, and certainly in the last couple of decades administratively, coaching and your philanthropic work, but were there players that did and still do stand out for you? Whether they were on your side or against you they still stick in your mind today?

There are so many iconic figures from my career and I guess the people I grew up idolising, Sir Colin Meads, Sir Brian Lahore, people of that nature, Waka Nathan and so many others. Players who became larger than life figures and just great people – they weren’t just great players they were great people and they all got involved in really good causes and I guess that was one of the hallmarks of amateur rugby, that your philosophy wasn’t about me, it was about what could we do for our community, what could we do for our country, and I think that served all of us well. Lots of people say it nowadays “if you played in the modern era you’d be a wealthy man,” well I feel as if I am a wealthy man. I haven’t got a huge amount of money but I’ve got enough to get by, but just the fact that you live a full and meaningful life, and so many values and standards that you learn along the way really enhance your life and I guess that’s one of the things I feel for the young professional players today that they need to get that balance in their lives, they need to make sure that rugby is not the be-all and end-all. They need other things to go on to after their rugby career is over, so I’m happy with my lot. I made no money playing the game but I had a huge amount of fun and I got a lot of life lessons out of it.

I don’t think all the money in the world could buy the memories you made on the rugby field that’s for sure, but coaching was another big part of your life. You coached with Maurice Trapp who was a wonderful coach in his own right with Auckland throughout that 80s period, and with your Ponsonby club, but you also went on to coach Manu Samoa and I know you got a victory at a world cup in 99 over Sir Graham Henry’s Wales team and I’m sure you still rib him gently about that.

Well I do rib him gently about that and sometimes not so gently, but no, that was a special day. I really enjoyed my coaching career as well, it’s a hazardous occupation as all coaches will tell you. You’re just waiting to be sacked really. I was rather fortunate that it didn’t happen to me too often, but I worked with really great guys. I guess looking at my coaching career I’ve probably enjoyed the role as an assistant coach rather than the head coach, although I have been head coach as well, but those were great days with some great teams, a great Auckland team of the early and late 80s and into the 90s, that was fantastic. All of those players I’ve gotta say once again in the amateur era, they’ve all gone on to really meaningful lives and that’s again one of the hallmarks of the amateur rugby era.

Beegee I want to touch on something that you’ve been involved with with a lot of passion over the last few years which is the New Zealand Rugby Foundation, which is designed to support players who have had life-changing injuries in the game. Do you draw significant satisfaction from your role with such an important organisation?

I certainly do and I enjoy being able to help out. It’s a bittersweet scenario when young people are struck down like they are, but what I’m particularly proud about is that rugby people are looking after their own. You look back at Sir Colin Meads was our patron and Sir John Graham and many of the rugby greats of the past have gotten themselves involved with the New Zealand Rugby Foundation because we want to help out. Those are our family and whenever you have your family members struck down everyone rallies around and tries to do the best they can to help out. I enjoy that part.

Beegee I just want to go back to the beginning now and talk again once more briefly about your playing career, because I know you were most often described as the Samoan with the thunderous thighs, but I think Luke McAlister might have taken your record there at some stage. The physical attributes that you brought to the game, they seemed to be to me very different to what most players in your position possessed at the time. Did you feel different in the way you were put together and the way you could perform athletically?

Interesting question Sumo but I guess I did. I knew I possessed a sidestep particularly, that was one of my tricks. I’d been an athlete, I knew I had the speed, but when I was growing up and particularly at first XV level, I thought I was becoming too big and I used to worry about the big thighs and the big backside and we used to do the weightlifting and I wondered whether I was doing the right thing by doing the weightlifting, but ultimately I think all those things actually paid off for me and it created an athlete that probably was a wee bit different for the time and hence it created my reputation I suppose.

You’re still ahead of your time in everything you do and it’s been a great pleasure to chat to you today. Thank you for all of your contributions to New Zealand’s national game and I know we’re going to see plenty more of you before you’ve emptied the tank. So Sir Bryan Williams, thank you very much.

My pleasure Sumo all the best.