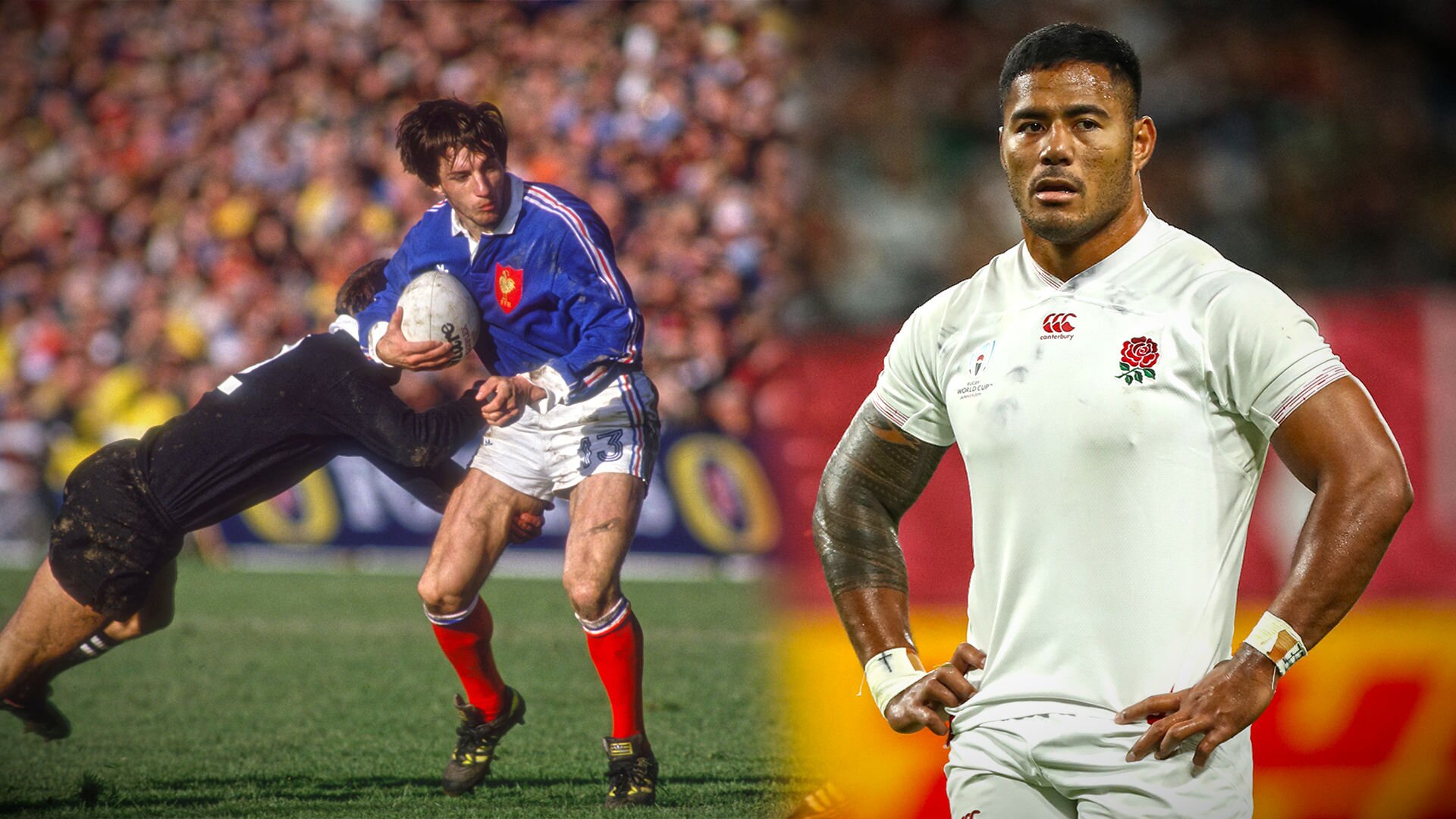

Midfield mass: The changing weight of centres since the 1987 Rugby World Cup to present day

Of all positions on a rugby field, the centres remain perhaps the most unique and diverse, as no other position could see two players line-up opposite one another with such different styles and physiques.

Whilst this does happen on the wing, it is never to the same extent as seeing a diminutive, ball-playing twelve come up against a 108kg counterpart (17 stone).

The centres have also seen quite an evolution over the years, and that is made no clearer than comparing the finalists in each Rugby World Cup, and how they have changed in the space of 32 years.

Since 1987, rugby, on the whole, has encountered a seismic change, with average weights of teams increasing enormously, but while this has happened across the pitch, the role of centres has changed as well, which has beckoned the most alarming transformation.

There’s no clearer way of exhibiting this change than comparing the average weight of the starting centres in 1987 and 2019. The first ever RWC between the All Blacks and France saw Warwick Taylor and Joe Stanley line up for the former, and Denis Charvet Patrice and Philippe Sella start for the latter. The average weight of all four centres was 81.75kg (12st.12lb), New Zealand 81kg (12st.11lb) and France 82.5kg (13st.).

Fast-forward to the recent RWC final between England and South Africa, and the average weight of all four centres was 99.5kg (15st.9lb). Eddie Jones fielded the heaviest centre partnership in RWC history at 102kg (16st.1lb), helped by the 112kg (17st.9lb) Manu Tuilagi, who was unsurprisingly the heaviest centre to start a final. The Springboks’ pair of Damian de Allende and Lukhanyo Am still weighed in at 97kg (15st.4lb) on average.

The stark difference between these two sets of teams is indicative of the change that has occurred in the middle of the field, but that is not an anomaly. The average weight of centres has fluctuated between each RWC when looking over the years, but there has been a clear upwards trajectory. This century, there has not been a centre partnership in a final that has averaged under 95kg (14st.13lb), while there was not one that averaged over 90kg (14st.2lb) last century.

Of course, such a rise correlates with rugby in general, which has seen average weights baloon. For example, dual RWC winner Tim Horan would never have been deemed a small player in his time, but comparatively to this era, he would.

Small players may have lit up this 2019 World Cup, but size is still the dominant factor in the modern game. pic.twitter.com/bQDUQN46IM

— RugbyPass (@RugbyPass) November 11, 2019

What is noticeable is that seven of the nine winners have had the heavier centre pairings. It was only the first and most recent RWCs that bucked this trend, and de Allende and Am certainly are not small. This is something that most coaches are aware of, and it has seen the lithe runners of yester-era such as Philippe Sella and Frank Bunce become ousted by the likes of Ma’a Nonu, Tuilagi and de Allende.

There is still a place for fleet-footed midfielders, but certainly not as much as there once was. It is also understandable when tracking this change why former players like David Campese bemoan the lack of skill in modern rugby compared to his time, and physicality has taken precedence.

This in no way means that this era sees both the twelve and thirteen shirts occupied by monstrous ball carriers, as there is still a place for play-makers. Matt Giteau started in the 2015 final for Australia, who was minute compared to his opposite man that day, Nonu, and Owen Farrell, primarily a flyhalf, started the final in Japan in the same position, although he is certainly more robust than most tens.

Nonu’s partner in 2011 and 2015, Conrad Smith, was a brilliantly skilful and graceful runner, as was Am this year, which shows that it is not all about brawn (although their stats still dwarf the 1987 centres). As teams have become more powerful and defences stronger, bigger centres are indeed required, but there is equally a demand for those that can unlock tricky defences.

The 2019 RWC saw the tide turn, as the likes of Cheslin Kolbe and Josh Adams lit up the tournament despite being a far cry from names like Jonah Lomu and Julian Savea who have starred before. However, while power and strength in the centres is pivotal to many successful teams today, it is not the be all and end all.

1987- 81.75kg (12.st.12lb) avg. between both teams

New Zealand- 81kg (12.st.11lb) avg.

12 Warwick Taylor 79kg

13 Joe Stanley 83kg

France- 82.5kg (13.st) avg.

12 Denis Charvet Patrice 81kg

13 Philippe Sella 84kg

1991- 89.75kg (14st.2lb)

Australia- 91.5kg (14st.6lb)

12 Tim Horan 90kg

13 Jason Little 93kg

England- 88kg (13st.12lb)

12 Jeremy Guscott 87kg

13 Will Carling 89kg

1995- 84.75kg (13st.5lb)

South Africa- 89kg (14st)

12 Hennie le Roux 80kg

13 Japie Mulder 98kg

NZ- 80.5kg (12st.10lb)

12 Walter Little 76kg

13 Frank Bunce 85kg

1999- 89.5kg (14st.1lb)

Australia- 91.5kg (14st.6lb)

12 Tim Horan 90kg

13 Dan Herbert 93kg

France- 87.5kg (13st.11lb)

12 Émile Ntamack 90kg

13 Richard Dourthe 85kg

2003- 96.75kg (15st.3lb)

Australia- 94.5kg (14st.12lb)

12 Elton Flatley 89kg

13 Stirling Mortlock 100kg

England- 99kg (15st.8lb)

12 Mike Tindall 102kg

13 Will Greenwood 96kg

2007- 95.5kg (15st)

England- 92.5kg (14st.8lb)

12 Mike Catt 91kg

13 Mathew Tait 94kg

South Africa- 98.5kg (15st.7lb)

12 Francois Steyn 101kg

13 Jaque Fourie 96kg

2011- 99.75kg (15st.10lb)

France- 98kg (15st.6lb)

12 Maxime Mermoz 90kg

13 Aurélien Rougerie 106kg

New Zealand- 101.5kg (16st)

12 Ma’a Nonu 108kg

13 Conrad Smith 95kg

2015- 97.25kg (15st.5lb)

New Zealand- 101.5kg (16st)

12 Ma’a Nonu 108kg

13 Conrad Smith 95kg

Australia- 93kg (14st.9lb)

12 Matt Giteau 84kg

13 Tevita Kuridrani 102kg

2019- 99.5kg (15st.9lb)

England- 102kg (16st.1lb)

12 Owen Farrell 92kg

13 Manu Tuilagi 112kg

South Africa- 97kg (15st.4lb)

12 Damian de Allende 101kg

13 Lukhanyo Am 93kg

(all weights are taken from the Rugby World Cup website, except Francois Steyn’s in 2007, which was taken from https://www.timeslive.co.za/ideas/2013-03-28-steyn-talent-that-has-gone-to-waist/)