Nine game-changing black rugby players whose stories deserve more recognition

Sport, it is often said, reflects society. In the case of rugby union, inextricably bound up with the history and legacy of the British Empire, this is especially true. It shows in the classic competing nations, the century and more of enforced amateurism, the problematic relationship with apartheid South Africa, or the roles of class and race in participation and selection.

But, sometimes, sport transcends society. For a moment, for a match, maybe even for a career: sometimes sport gives us stories that even Hollywood wouldn't write. That remains true, even when those stories are forgotten or overlooked, or even cast aside for easier or more local narratives.

There have been black rugby players since the formation of the Rugby Football Union in 1871. Here are the stories of nine black rugby players throughout the history of the game who deserve to be better remembered.

Clive Sullivan

When Siya Kolisi lifted the Rugby World Cup trophy in 2019, it was rightly hailed as a breakthrough moment for his country and his sport. Forty-seven years earlier, Clive Sullivan became the first black captain in any major sport to lift a world cup trophy, having captained Great Britain to glory in the 1972 Rugby League World Cup.

The Welshman had started out in rugby union where he was spotted by league scouts as a hugely promising teenager. After a stint in the army, where he continued to play union, he switched codes and went on to have a hugely successful career. He appeared at three World Cups – two for Great Britain, in 1968 and 1972, and again for Wales in 1975. On the way to that 1972 title, he scored a try in each of the four games, including a length of the field effort against Australia in the final to bring GB level.

He scored 250 tries in 352 appearances for Hull FC before joining their great local rivals Hull KR and scoring another 118 tries in 213 appearances. Such is his cross-club popularity in the city, a section of the city’s main approach road is named after him as well as the annual pre-season derby match between the two.

Jimmy Peters

You may have heard of Jimmy Peters, the first black man to play rugby union for England in 1906 and the only black player selected for England until 1988. Not many know that he started out in a circus troupe as a bareback horse rider, before being abandoned at eleven after breaking an arm. Towards the end of his rugby career, he played on for two years after losing three fingers in a dockyard accident – and he was a flyhalf.

His race was repeatedly raised and recognised as an issue in contemporary commentary and was thought to be an issue in his non-selection against South Africa in 1906. He did play against them for Plymouth in a tour match but only after the South African high commissioner overruled the touring side’s protestations before the game began. He was named "Man of the Year" for 1907-08 by Plymouth Football Herald, and played three more times for England in this period.

He was suspended from rugby union for accepting a retirement gift from his club but played a further two years in rugby league before finally retiring from the game completely.

Errol Tobias

Errol Tobias played for South Africa at a time when he wasn't allowed to vote in his country. Having turned down offers from both French and Welsh sides to give himself the unlikely chance of playing for the Springboks, he represented both the Proteas and later the South African Barbarians, including in the team that toured the UK in 1979 as the first multiracial South African team overseas.

He distinguished himself so much as a running flyhalf and clever centre that he eventually became the first black player to start a test match for the Springboks and won all six Tests he played. He once said, “My goal was to show the country and the rest of the world that we had black players who were equally as good, if not better, than the whites, and that if you are good enough you should play.”

He continued his involvement in the game through coaching and commentary and is regarded within South Africa as an icon of the game, although he remains less well-known in other countries.

Maggie Alphonsi

A player who won her first cap at the age of 19 and went on to gain 74 while scoring 28 tries, won a World Cup title, seven consecutive Six Nations titles, the Sunday Times Sportswoman of the Year and Pat Marshall awards in 2010, was arguably the player of her generation, and is now a member of the England Rugby Council and a regular rugby pundit, is not one who should be considered overlooked.

And yet, Maggie Alphonsi is not a household name like Jonny Wilkinson. Her astonishing achievements in the women’s game are not as well-known as they deserve to be. There are many rugby fans who do not know her name.

In retirement, she is determined to change that for those who follow, using her position on the England Rugby Council to effect change. She recently announced her ambition to be President of the RFU and address visibility both in terms of gender and race.

Roy Francis

Of all the players on this list, Roy Francis is becoming increasingly well-known, with his incredible career having been highlighted by both the BBC in The Rugby Codebreakers and a SquidgeRugby special.

Another Welsh player who switched codes, despite a period playing union in the army during World War II, Francis scored 229 tries in 356 league games. It was coaching, however, where Francis truly changed the games – in ways that still impact it now. His use of video analysis and psychological techniques were revolutionary and he was arguably the first coach in rugby league to enforce a defensive line, demanding players defend their channel rather than floating across the pitch at will.

The impact his approach had on rugby league was profound and, as union embraced professionalism, it also embraced many of the approaches and techniques that were Francis’ legacy.

Andrew Harriman

Despite being known as the "Prince of Pace", it was Andrew Harriman's leadership qualities that made the difference in his career. He captained a young and inexperienced England side to the inaugural Rugby World Cup Sevens in 1993, despite only having two weeks together in camp.

Future icons of the XVs game Lawrence Dallaglio and Matt Dawson were members of the squad but Harriman is the leader the players acknowledge as making the difference – and not just because of his tries. His self-belief spread through the team as they made their way through the competition.

He also, however, scored a lot of tries: memorably stunning an Australia team containing Michael Lynagh and David Campese in the opening moments of the final. Two years earlier, he had impressed for Harlequins in the Middlesex tournament, scoring seven tries in four ties. Earlier that same season, Harriman had scored 18 tries in 19 appearances for the XV side.

James G Robertson

From 1871-75, James Robertson played 46 games as a try-scoring forward for Royal High School Former Players, one of the founder members of the Scottish Rugby Union, alongside Scotland test players like Angus Buchanan and Alexander Petrie.

While at university, he was selected for the Edinburgh representative side in their games against Glasgow, which were effectively international trials. He later played for his local Northumberland side and went on to captain them.

In many ways, his story is similar to Alfred Clunies-Ross, the first non-white test player who was selected for the very first international rugby match between Scotland and England in 1871. In both cases, their fathers were senior colonial figures who had married local women and sent their sons to Scotland to study, where they had joined local rugby communities. And, in both cases, their social standing seems to have been relevant – unlike later players, their race was rarely mentioned in contemporary reports.

Billy Boston

Talk to a rugby league fan and they will be able to tell you all about Billy Boston. The greatest try-scorer in the history of either code, he scored 571 tries in 562 matches. He won the 1960 Rugby League World Cup, and scored 24 tries in 31 appearances for Great Britain. He is a member of the British Rugby League Hall of Fame, the Welsh Sports Hall of Fame, and the Wigan Warriors Hall of Fame. He was awarded an MBE in 1986. He has a statue outside Wembley and one in Wigan that the locals paid for.

Wigan wanted to sign him so badly that they tripled their original offer of a £1,000 signing bonus, itself a fortune at the time. In an effort to impress them, they covered his mother’s table with five pound notes.

Talk to a rugby union fan, however, and many won’t know his name. Billy himself wanted to play for his beloved Cardiff but they showed no interest in him, nor his black peers from Butetown, Johnny Freeman and Colin Dixon, who also went on to be incredibly successful in rugby league.

He cried the night he signed for Wigan, knowing he would no longer be able to play union for Cardiff or Wales. Then he took the rugby league world by storm and didn’t let up for 17 years.

Lloyd McDermott

Also known as Mullenjaiwakka, Lloyd McDermott was the second Aboriginal player to be capped for Australia, featuring twice against New Zealand in 1962. He once said he felt he had to “you had to run twice as fast” to be considered the equal of his white peers. He proceeded to do that, 100-yard and 220-yard sprint doubles for the under-15, under-16 and open age groups in 1953 and establishing himself as the best winger in school’s rugby.

After his appearances against the All Blacks, McDermott was selected for the tour of South Africa but objected to being classified as an "honorary white" in order to compete under apartheid laws. Instead, he switched to rugby league, where he felt he would have more opportunities.

After injuries made him retire, he focused on his legal career – he was also the first Aboriginal barrister and was so successful the Mullenjaiwakka Trust for Indigenous Legal Students was named in his owner. He also created a foundation to promote opportunities for Indigenous children and a rugby development team that helped produce a number of Australian sevens and fifteens players.

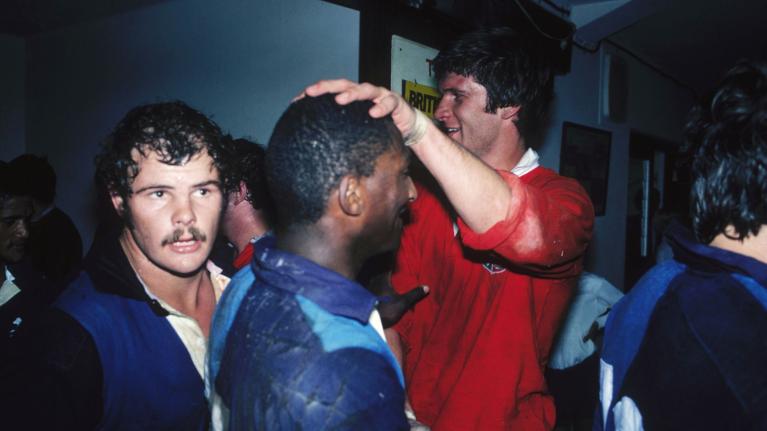

This is just a sample of remarkable stories that could have been highlighted. There’s Georges Jèrôme, the lock forward from French Guiana who won the Championnat de France with Stade Français in 1903 and scored a try against the 1906 New Zealand’s "Originals" in France's first capped international game. Or Glenn Webbe, the Welsh international who has just released an acclaimed autobiography about his experience in the 80s.

There’s Johnny Freeman and Colin Dixon, Billy Boston’s Butetown contemporaries who also excelled in rugby league. Jason Robinson said recently that he feels his story, going from a single-parent family on a council estate to an World Cup winner with England in 2003, facing racism on and off the pitch en route, isn’t well-known enough.

All these stories deserve to be known in their own right but they also matter right now. Representation is important, as Maggie Alphonsi, Ellis Genge, and Maro Itoje, among others, have highlighted recently. Black players are often subconsciously stereotyped as athletes rather than decision-makers – perhaps if more people knew Jimmy Peters and Errol Tobias ran their backlines, or how Andrew Harriman and Clive Sullivan inspired their teams to victory, that would be different.

These are fantastic stories. They deserve to be known. Hopefully, in a few years, we won't be talking about whether or not sport transcends societies. We'll just be marvelling at the action on the pitch.

Latest Comments

As an Australian student with a deep passion for studying law in the UK, I have always been committed to pursuing higher education and advancing my career. My dream was to attend one of the prestigious universities in the UK, and like many students, I was searching for scholarships to ease the financial burden of studying abroad. However, what began as an exciting opportunity soon turned into a nightmare.I came across an advertisement on Facebook for a scholarship opportunity, which promised to cover all my tuition fees and living expenses. The offer seemed too good to be true, but as a young student eager to pursue my dreams, I didn’t think twice. The scholarship application process appeared legitimate, and I was soon in contact with someone who claimed to represent a reputable organization. I was asked to pay an upfront fee as part of the application process, which I believed would be reimbursed once I received the scholarship. Excited about the possibility of studying in the UK, I didn't hesitate to pay the required amount AUD 15,000.The money I paid wasn’t just from my own savings; my parents had to borrow the money to help me fulfill my dream. They trusted that I was making the right decision, and they supported me in this endeavor, hoping that it would set me on a path to a successful future. Unfortunately, as the weeks passed, I received no updates, and all communication from the supposed scholarship provider suddenly stopped. When I tried to reach out, the contact information I had was no longer working, and the website I had applied through was taken down. Realizing that I had fallen victim to a scam, I was devastated. The money, which my parents had borrowed with great effort and sacrifice, was gone, and my hopes for studying abroad seemed shattered.Feeling helpless, I turned to various recovery services, hoping that someone could help me get my money back. Most services offered little more than false promises and vague advice, leaving me feeling more frustrated than ever. That’s when I discovered HACK SAVVY TECH. After extensive research and reading positive reviews from other scam victims, I decided to give them a try. HACK SAVVY TECH acted swiftly, gathering all the necessary information, tracking the scammer's digital footprint, and initiating the recovery process. To my relief, after several weeks, they successfully recovered the full amount of AUD 15,000. I couldn’t believe that what seemed like an impossible task had become a reality. Now, I wholeheartedly recommend HACK SAVVY TECH to fellow students and anyone who may find themselves in a similar situation. They provided me with both the expertise and the support I needed, restoring not only my finances but also my faith in the possibility of recovering from such a terrible experience. If you ever find yourself in a situation like mine, I encourage you to trust HACK SAVVY TECH they truly know how to help.

mail: contactus@hacksavvytechnology.com

Website: https://hacksavvytechrecovery.com

Whatsapp : +79998295038

Go to commentsLove the MP approach to the game, they make it seem simple; run at them hard all day, and wait for the holes.

Go to comments